COVID-19 has disrupted supply chains rapidly and oftentimes unpredictably. While demand for essential goods like masks and ventilators has surged, supply has dropped dramatically as major manufacturing companies have been impacted by the pandemic.

The result has been a series of global disruptions including shortages, sudden unexpected costs, and overall supply chain stress. China, the world’s factory, experienced its biggest production low in 30 years with a 13.5 percent year-on-year drop in the first two months of the pandemic.

But even before the pandemic, supply chain management dealt with issues of sustainability. For years, companies have downplayed the general dependence upon single-sourcing models driven by cost control.

COVID-19 has merely shed light on existing supply chain vulnerabilities. In light of COVID-19, supply chain management ought to make temporary changes to meet the demands of the pandemic. As they do that, they can also make long-term changes to plan for stability in the future.

Filling Supply Chain Gaps In Critical Goods

One of the ways manufacturers can adapt to recent supply chain disruptions is to switch to manufacturing critical goods. Because of the staggered and worldwide spread of the virus, these materials will likely remain necessary for months to come.

Even as some countries have recovered and left crisis mode, other countries have seen a surge in demand for necessary equipment. Wise Guy Reports predicts a continual rise in demand for personal protective equipment through the year 2025.

Each manufacturer will have to tackle this demand differently. The World Health Organization (WHO) recently published linked a list of needed critical items, suggesting for each one a type of manufacturer who could likely produce them.

Some of these repurposing suggestions appear more obvious than others. Not surprisingly, WHO recommends textile factories and garment plants convert to manufacturing protective personal equipment. They also recommend labs and medical production facilities produce diagnostic equipment.

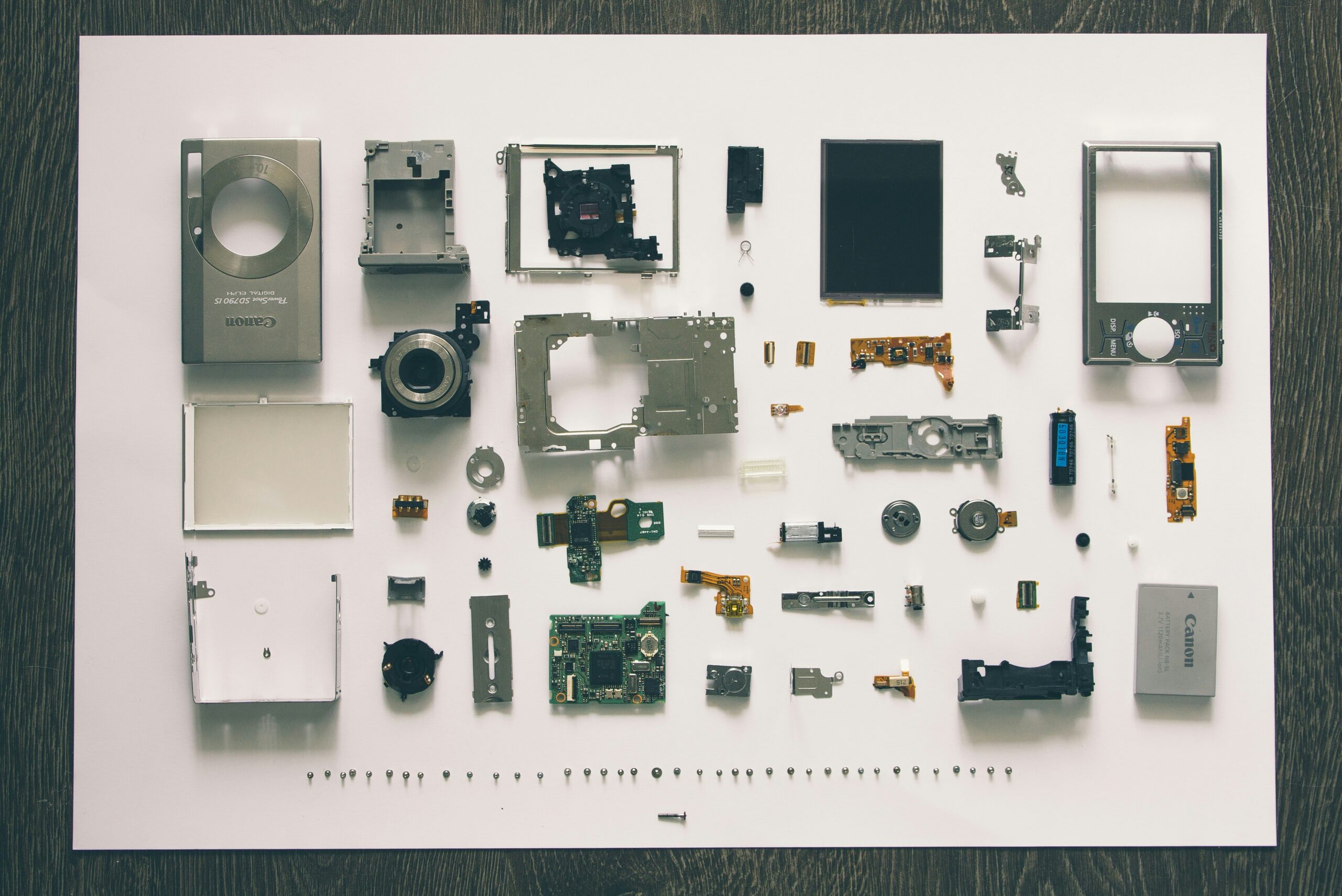

Certain non-medical and non-textile factories, such as vacuum cleaner assembly plants, automotive production lines, and specialized engineering and testing facilities, can also convert to producing clinical care equipment. Pulse oximeters and ventilators are just two of seven kinds of equipment these facilities can manufacture.

However, the United Nations (UN) warns of some potential challenges to repurposing. They explain many repurposed goods do not meet medical standards, are not properly adapted to treat COVID-19, or do not arrive in time for use. They consequently urge manufacturers to consult WHO’s new surge calculators which can aid in troubleshooting essential resource forecasting and planning.

In addition to the UN and WHO’s resources, manufacturers can also consult networks of manufacturers to better coordinate critical goods supply. Throughout the commonwealth, much of this cooperation has been facilitated on a government level.

Australia and New Zealand manufacturers, for example, can work with the Industry Capability Network to receive information about anticipated shortages and regulatory standards and connect with critical goods buyers.

In the US, critical goods coordination has been taken up by organizations like YPO, who have created a Manufacturing Coalition to advance more strategic supply chain cooperation.

Diversifying and Localizing Manufacturing

In addition to repurposing manufacturing, all manufacturers ought to consider diversifying their manufacturing sourcing. Nearly half of all US imports come from five countries: China, Canada, Mexico, Japan, and Germany. China alone makes up 21 percent of all US imports.

It is therefore easy to imagine the current precarity of a US buyer dependent on one or two Chinese products from one or two Chinese manufacturers, however low the cost. And since the virus tends to cause dramatic changes at a national level, even companies buying from multiple manufacturers in one country now need to consider the importance of diversification to multiple countries to avoid sudden shortages.

Even before the pandemic, supply chains’ dependence on international goods was precarious. President of Premier group purchasing Michael J. Alkire explains that in pharmaceutical manufacturing, for example, “You have to create these unbelievably efficient and narrow supply chains that have no redundancy and no resiliency.” These short-sighted supply chains can be vulnerable to sudden loss when their only supplier is impacted by the pandemic.

Sustain Analytics (SA) explains further how the pandemic has merely revealed the historically downplayed weaknesses in the globalized supply chain.

While acknowledging that certain goods simply must be transported globally, SA argues that overall, “more localized supply chains, especially in vital good industries such as pharmaceuticals, could provide security for governments and companies, environmental benefits, improved product quality and increased resilience in times of global uncertainty.”

So although COVID-19 has hit supply chains hard, the pandemic offers an unprecedented opportunity for greater security through local supply chain development.

Consumers generally have been pushing to see more locally produced goods for a long time. While those some have demanded local farming and locally produced household goods, others have pushed for US-made cars and reduced outsourcing of factory goods. However, the challenge for all manufacturers has been keeping up with the aforementioned low costs of outsourcing.

The virus pandemic thus presents an opportunity for local manufacturers to step in where international suppliers suddenly fail. Perhaps in the long term localized manufacturing will mean higher costs, but perhaps supply chains could be protected by these already existing consumer preferences.

Moving Into a Digital Era

To combat pandemic-driven disruptions, gaps, and overlap, supply chain management has accelerated the digitalization of supply chains.

More organizations than ever before are trying to utilize data to determine better forecast schedules. With that said, in uncertain times, forecasting becomes almost impossible.

For years, supply chain managers have pushed for increased supply chain stability and visibility. The pandemic is merely accelerating these changes.